SVEs represent an attractive simple element of remuneration for executives that can be introduced for no additional cost. They can also help address deficiencies with STVR and LTVR that are problems for some companies.

GRG Remuneration Insight 157

by Denis Godfrey & James Bourchier

19 February 2024

For many years institutional investors and governance groups have been against the use of Service Vesting Equity (SVE) grants, particularly for Chief Executive Officers; on the basis that it has insufficient links to performance and shareholder alignment. However, recent experience indicates that this may be changing, at least in the case of some groups, though in limited circumstances and where the rationale is carefully communicated.

This GRG Remuneration Insight discusses why service vesting equity should be considered as part of total remuneration packages for all executive roles.

What is Service Vesting Equity (SVE)?

Service Vesting Equity or SVE is a share-based payment arrangement where a participant may be entitled to receive equity if service related vesting conditions are satisfied, meaning the participant must remain employed by the company for a period of time to receive the benefit. SVE has no other vesting conditions attached, such as performance related vesting conditions.

The Background: Changing Market Conditions and Practices

After years of opposition, SVE became a standard part of executive remuneration as ASX 300 companies responded to the demand for Short Term Variable Remuneration (STVR) to be partly deferred. The rationale for acceptance in this case was that performance had already been tested for this component of the remuneration, and it was not additional remuneration. Instead, it was exposing amounts that would otherwise be settled in cash to market forces, clawback, and deferral.

Soon after, certain board advisors encouraged a group of listed companies to try to “simplify” their variable remuneration practices by eliminating Long Term Variable Remuneration (LTVR) and rolling all variable remuneration into so-called Single Incentive Plans (SIPs), which were initially no different from STVR with deferral into equity, except for the introduction of longer deferral periods. These were generally not well regarded, as it became apparent that executive remuneration varied almost entirely in relation to short-term and often internal views of performance only, and long-term alignment with the shareholder experience was lost.

As a result, most SIPs evolved to subject a portion of the deferred STVR amount to the same metrics as would apply to traditional LTVR, although the portion of remuneration subjected to long-term outcomes was generally substantially reduced compared to discrete STVR and LTVR structures, and the SVE component significantly increased. Interestingly, Proxy Advisors and institutional investors have tended not to vote against these structures, although most have been removed/replaced due to other shortcomings of this type of arrangement – such as when short-term performance has been poor (in which case all long-term alignment is also lost because there are little or no awards to defer into equity, performance tested or otherwise).

During the COVID crisis, two practices emerged that involve service vesting equity.

- Companies sought to reduce cash fixed pay to preserve limited cash-flow from reduced revenue. SVE as Fixed Pay was successfully used to replace cash Fixed Pay, producing improved alignment and attractive tax outcomes for all stakeholders in many cases. Just like Fixed Pay, employees needed to serve out a year in order for the equity to vest (become paid), with pro-rata forfeiture at termination (to ensure equivalence with cash Fixed Pay). Some companies have continued to use equity as part of Fixed Pay in the years since, in some cases in lieu of large cash increases as benchmarks are strongly rising. When the remuneration is not additional remuneration, and is clearly part of Fixed Pay, these arrangements tend to be well supported by external stakeholders.

- With the war for limited talent reaching a peak, more companies than ever started to pay sign-on and retention grants in the form of SVE. This area has remained contentious in the case of CEOs and other top executive roles, with different governance and investor groups taking differing views on these types of arrangements:

- Some appear to accept that these arrangements are now a necessary part of the remuneration landscape if top talent is to be secured in a competitive market. Some companies are offering these arrangements to critical talent across most levels of the organisation, as offering these arrangements to executives is consistent with their general practices. Sign-on and retention equity is particularly prevalent in the technology sector, and in companies with exposure to the USA market.

- Some appear to continue to oppose these types of grants where these types of arrangements appear to be additional remuneration to a regular or typical package for the role, and especially where there is no link to shareholder value. There have been many cases where CEOs and other top executives have received sign-on and retention bonuses that have fully vested in a year, or in some cases less, and have left with those amounts having paid out, having destroyed significant shareholder value, and having only served a short-term with the company. Long periods of service testing, and “up-side-only” structures like options or Share Appreciation Rights (SARs) tend to have faced lesser opposition in these cases, due to ensuring some alignment with shareholders.

Equity Aligns Executive and Shareholder Interests

When executives hold shares or fully vested rights or SVE (at least to the extent that the service vesting period has elapsed) they tend to consider themselves to be shareholders and therefore have similar interests to shareholders. By contrast, executives who hold performance vesting rights of the type typically granted under LTVR plans, or deferred STVR equity subject to long service conditions, do not feel that they are shareholders until the rights have vested due to the high risk of forfeiture (under traditional approaches). In addition, it is currently challenging for executives to meet shareholding requirements within the typical 3-year requirement, unless they have access to salary sacrifice equity plans, or can elect to receive all STVR awards in equity that is not at-risk (such as restricted rights with the minimum holding period required to access tax deferral).

Thus, by introducing SVEs companies will much more quickly achieve a position where executive and shareholder interests are aligned.

When Business Cycles do not Align with LTVR Measurement Periods

At a broad level, companies may be divided into three categories being:

- Those that are implementing/pursuing business strategies that, if successful, will result in a major change in shareholder value e.g., resource exploration, information technology, and biotechnology companies,

- Those that are pursuing gradual improvement to deliver sound returns to shareholders via dividends and share price growth, and

- Those where share prices are relatively inelastic compared to the market generally e.g. utilities.

The typical design of most LTVR plans is particularly suitable for companies in category b) above. These plans have annual grants of equity instruments, 3-year measurement periods, creating overlapping cycles, and performance metrics that typically include a Total Shareholder Return (TSR) metric and a financial metric.

The typical design of LTVR plans is generally less suitable for companies in category a) above. This is because the period to achieve success would rarely be 3 years, executives join the company at different times in the journey to success, performance metrics other than perhaps TSR are rarely relevant as these companies are often loss-making during the journey to success.

For companies in category c) above, the use of relative TSR scales generally does not produce vesting results that correctly align with performance. This is because when the market is rising, they tend to underperform the market even when the company is performing well and when the market is falling, they tend to outperform (fall less) the market. This gives rise to nil vesting in a rising market, and potentially high vesting when the market is falling with no relationship to company performance. Further, in a falling market the TSR outcome is likely to be negative which would in many cases result in nil vesting, via a positive TSR gate. A “lose-lose” situation for executives working in utility companies with typical LTVR plans.

For companies in all categories there are good reasons to include SVEs as an element of remuneration, however for companies in categories b) and c) there may be a case for the SVE element to be a much higher percentage of Fixed Pay than STVR (often not appropriate for category b) companies if they are loss-making) and LTVR.

Retention Impact

A hangover from old-fashioned LTVR plans is that grants are forfeited on cessation of employment except in special circumstances (death, TPD, retirement etc). This approach has led to many executives considering LTVR grants to be of little or no value due to the likelihood of forfeiting all, but the first two grants when their tenure falls in the typical range of less than 5 years. With properly structured SVEs, there is no risk of forfeiture of grants that have been earned with service, assuming some of the grant is considered earned with each passing year. Thus, executives will fully value these grants. As a result, executives will see their total remuneration packages as being more attractive and therefore more likely to help in the attraction and arguably retention of these executives, despite the fact that they will not lose much of this remuneration at termination i.e. because the package is more attractive than offered by competitors.

Financial Planning

From FY24 onwards there will be virtually no opportunity (max. of $101 in FY24) for executives to salary sacrifice into superannuation to supplement the maximum amount that must be contributed under the Superannuation Guarantee Contribution (SGC) laws. For most employees, the SGCs are unlikely to produce a sufficiently large investment to cover their needs in retirement. In the case of executives this situation is exacerbated by the fact that the SGCs decrease as a percentage of fixed pay, let alone total remuneration packages, as remuneration increases above the SGC contribution limit of $249,000 in FY24.

If SVEs were to be introduced, then they could be accumulated by executives over their working life to produce an investment portfolio that will enable them to maintain their lifestyles into retirement. As tax on SVEs cannot be deferred for more than 15 years it follows that no later than 15 years from grant, executives will need to exercise rights into shares, some of which may need to be sold to pay tax on the benefit. Others may be retained or sold to diversify the executive’s investment portfolio.

The advantage of SVEs over LTVR grants is that executives are provided with greater certainty as to their entitlements, and therefore can undertake prudent financial planning. Executives could also re-negotiate their Fixed Pay to include SVE in lieu of elective superannuation contributions that are now severely limited.

Possible New Mix of Remuneration Elements

If SVE grants were to be introduced as part of typical executive remuneration, then the following elements would constitute a total remuneration package:

- Fixed Pay,

- Short Term Variable Remuneration (STVR) or Short Term Incentive,

- Service Vesting Equity (SVE), and

- Long Term Variable Remuneration (LTVR) or Long Term Incentive.

It is not being proposed that total remuneration packages be increased but that the mix of elements be changed. The percentages that the elements represent of the total remuneration package should be structured to best meet the specific needs and circumstances of each company.

In this regard, it should be noted that with an average executive tenure of less than 5 years, it follows that equity holdings from performance vesting LTVR grants will not arise until the fourth year of service, and shareholding policies typically allow for a similar period, which means that alignment of executive and shareholders interest via the holding of shares acquired under LTVR plans will on average exist for less than 40% of the executive’s tenure.

Deferral of part of STVR awards into SVE is less than ideal because:

- The quantum of STVR awards can fluctuate from year to year with the result that the quantum of SVE also fluctuates,

- Attaching a service vesting condition to deferred STVR awards is adding another condition to be met before the executive becomes entitled to the reward – this is arguably not appropriate given that the STVR award has been earned with performance, and under the current regulatory frameworks, Restricted Rights (disposal and/or exercise restrictions but no service conditions) is the ideal and fairer way to defer earned STVR,

- Delaying the grant of the deferred equity until after the end of the year means that alignment of executive and shareholder interests is delayed for a year compared to when SVE grants are made at the beginning of the year.

While deferring STVR has some good features and is often required of ASX 300 companies with high institutional investor exposure, it reduces clarity as to the purposes of remuneration elements if the deferral is subject to service testing. Therefore, consideration should be given to other methods of providing SVE, rather than relying on STVR deferral.

Of course, when equity is provided as part of remuneration the company will experience cashflow savings even though the accounting cost will be the same whether the remuneration is in cash or equity except that equity expensing may be spread over several years. Tax deductions for equity remuneration usually require the use of an employee share trust and can be larger than for cash remuneration, which can be a net/comparative cost advantage, but can be delayed for years.

Illustrative Example

Following is an example of how SVEs could be operated as part of a market competitive total remuneration package.

- The company decides that SVEs with an annual value of 20% of the executive’s Fixed Pay will be provided as part of the executive’s total remuneration package.

- The Board believes that share price growth over the coming years will be at least consistent with broad market movements in share prices. With this in mind, the Board decides to grant rights with a value equal to 60% of the executive’s Fixed Pay to cover 3 years of SVE remuneration.

- The rights will vest after 3 years of service. If the executive leaves employment with the company before the end of the 3 years, then pro-rata vesting will apply, and the remainder will be forfeited.

- Dividend equivalent payments will be made by the company in respect of vested rights and unvested rights with dividend equivalents being made on one-third of unvested rights in year 2 and two-thirds of unvested rights in year 3.

- Receiving dividend equivalent payments should remove any preference that the executive may have to hold shares rather than rights, and ensure that rights are not exercised until the executive wishes to sell shares. Exercise of the rights would trigger a taxing point, so delaying it for as long as possible (maximum of 15 years) enables the executive to maximise benefits from share price growth and dividend equivalents.

Fewer Rights to be Granted

When calculating the number of performance rights to be granted under LTVR plans, the typically used formula is:

| Number of Rights | = | Stretch Award Opportunity ÷ Right Value |

In order to calculate the number of rights to be granted, when a binary vesting condition such as service is attached requires deconstruction of the “Stretch Award opportunity” element. This element is calculated as:

| Stretch Award Opportunity | = | Target Award Opportunity ÷ Target Vesting Percentage |

Applying this formula to performance vesting rights, which typically have target vesting of 50% and service vesting rights which have a 100% target vesting percentage produces the following outcomes.

| Stretch Award Opportunity | = | Target Award Opportunity ÷ Target Vesting Percentage | |

| Performance Vesting Rights Stretch Award Opportunity | = $1,000 ÷ 50% = $2,000 |

| Service Vesting Rights Stretch Award Opportunity | = $1,000 ÷ 100% = $1,000 |

As the maximum value to be provided in rights is halved for service vesting rights the number of rights to be granted is also halved. Thus, by replacing performance vesting rights with service vesting rights – the total number of rights to be granted will be halved.

Simplicity

An advantage of SVEs is that the terms of the offers including vesting conditions are less complex than the performance conditions that form part of STVR and LTVR plans, in companies where external stakeholders will accept that either or both of these structures are not appropriate to the business at the time.

Tax Efficient

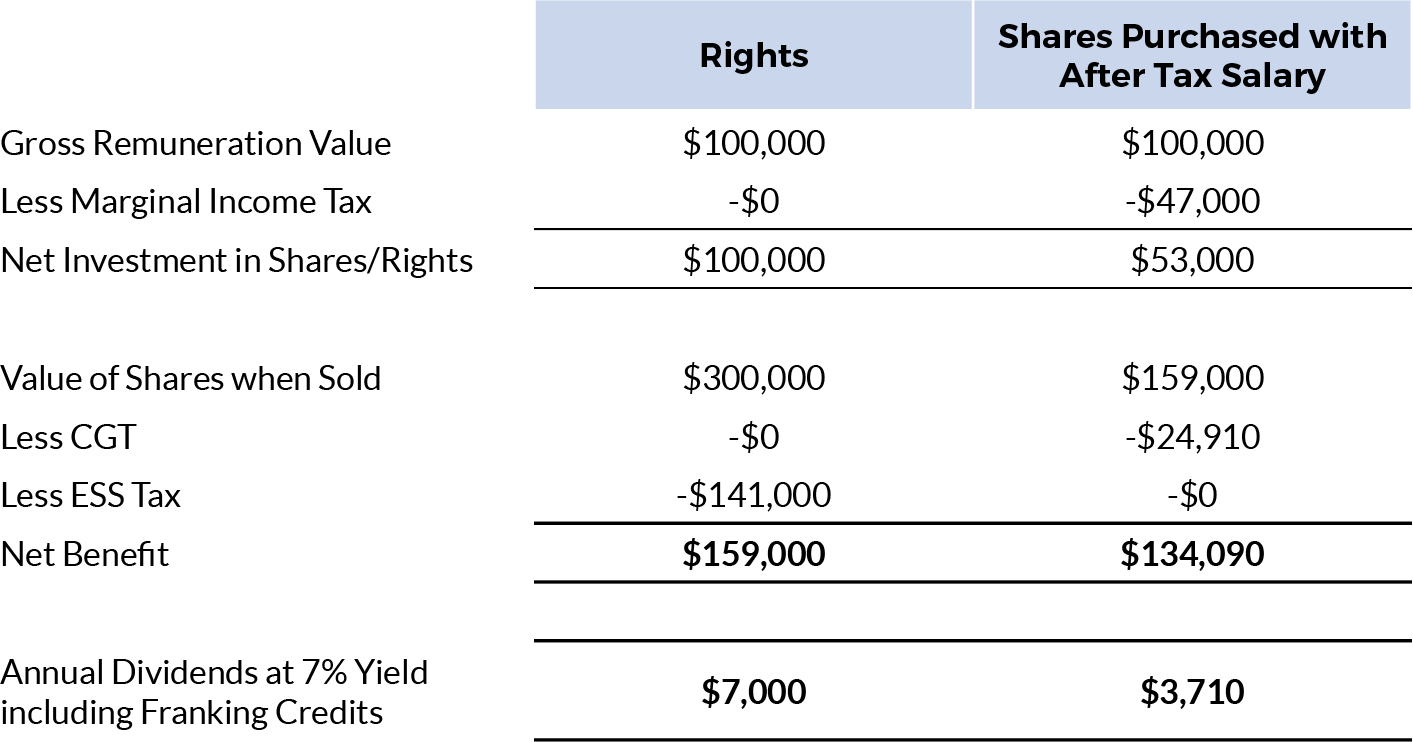

Rights that qualify for tax deferral are a tax efficient form of remuneration, as demonstrated in the following simple example. The comparison is between an executive who receives rights as part of remuneration, and one who receives an equal amount of salary and applies the after-tax salary to purchase shares.

The two points to note from the example are:

- Rights outperform the after-tax investment by the amount of CGT that is not payable, and

- The dividend equivalents received in relation to rights are approximately double the amounts of dividends and franking credits received from shares.

Conclusion

SVEs represent an attractive simple element of remuneration for executives that can be introduced for no additional cost. It can also help address deficiencies with STVR and LTVR that are problems for some companies.