SIPs may at first glance seem to offer less complexity and more certainty than commonly accepted STI and LTI plans, but they are actually more complex and lead to lower payments for executives than expected.

GRG Remuneration Insight 152

by Denis Godfrey & James Bourchier

24 November 2023

Single Incentive Plans (SIPs) are being operated by a small number of ASX-listed companies. SIPs involve the aggregation of short term incentives (STI) and long term incentives (LTI) into a single plan where awards are delivered predominantly in equity, but typically also partly in cash at the end of each financial year. Performance is primarily measured over a single financial year to determine the amount of the award in much the same way as STIs normally operate.

SIPs seem to have been sought by executives who expect more certainty as to the value of remuneration that is earned compared to remuneration that includes separate STI and LTI plans. The perceived uncertainty and complexity that surrounds vesting of LTI grants can be better addressed by improved LTI plan design and communication, rather than by absorbing the LTI into a SIP – but that is not the topic of this Insight. Proxy advisors and other external stakeholders have generally not supported the use of simple SIPs (without long term performance metrics) because they have an excessive focus on short term results but often accept them when part of the award is delivered in Performance Vesting Equity (PVE), which most SIPs now do. It is this PVE that leads to lower executive remuneration compared to a discrete LTI opportunity or grant, when target performance is achieved i.e., in a typical scenario.

The Conversion of STI and LTI into a SIP

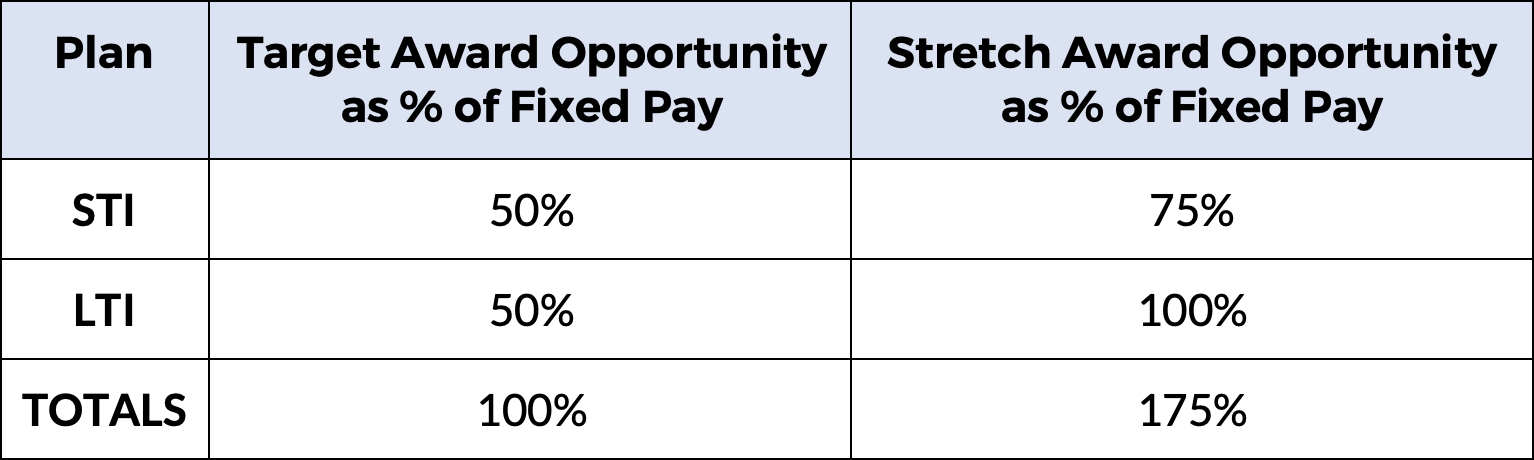

When STI and LTI are converted into a SIP it is generally seen as an underlying principle that the change should not result in any variation to the target or stretch levels of award opportunity. To illustrate it is assumed that an executive had the following award opportunities:

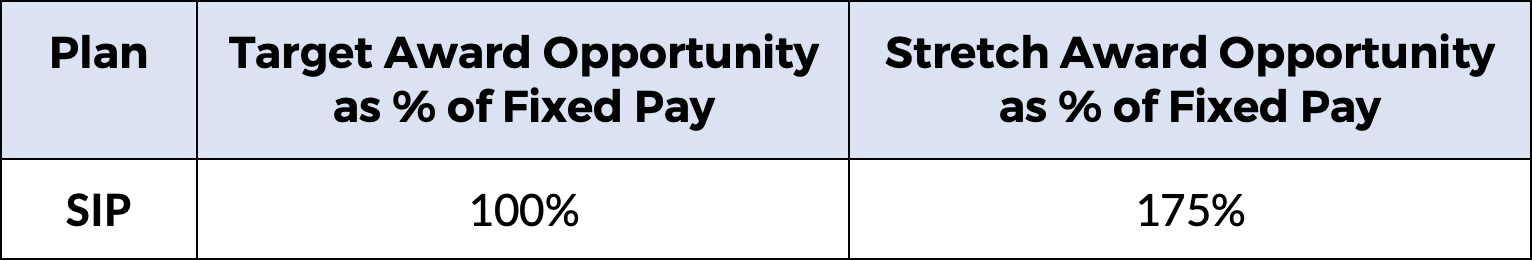

To achieve a conversion of STI and LTI into a SIP in accordance with the above-mentioned underlying principle would require the following award opportunities:

Delivery of SIP Awards

Delivery of SIP Awards occurs following the end of the financial year and tends to be divided into up to four elements as follows:

- Cash,

- Fully Vested Equity (FVE), such as “Restricted Rights” with no service conditions,

- Service Vesting Equity (SVE), such as “Service Rights”, and

- Performance Vesting Equity (PVE) such as “Performance Rights”.

Assuming equal division of awards, the following opportunities would apply at target and stretch:

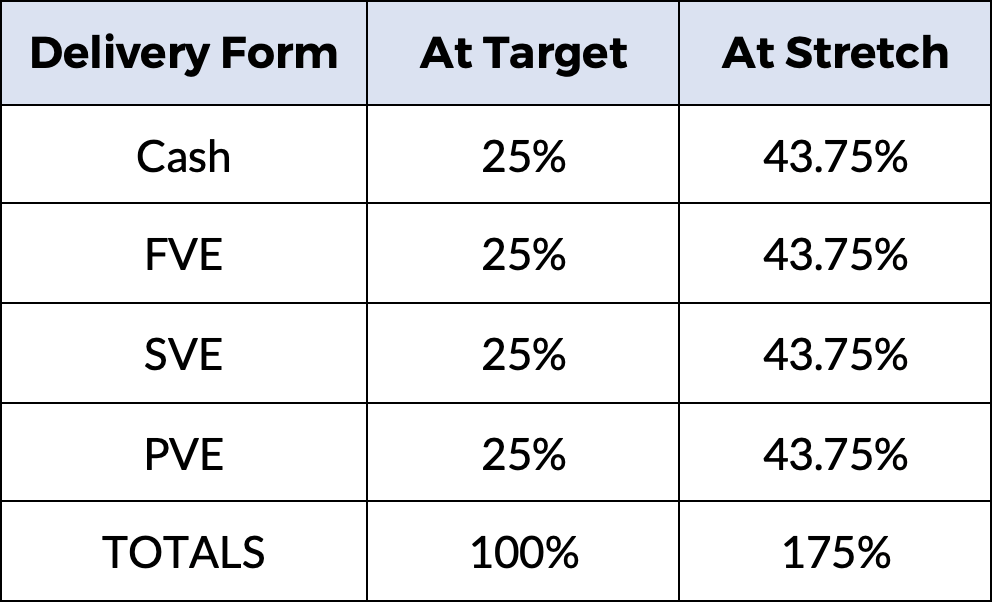

For cash, FVE and SVE the conversion is straightforward as the value received equals the value of the award allocated to that form of delivery. However, PVE is a more complex matter.

If PVE is subject to the types of performance vesting conditions that is normally attached to LTI grants, such as a Total Shareholder Return vesting scale, the typical value of the grant is around 50% of the face value of the grant because it is generally unlikely that more than 50% of the grant will vest. This is also the typical discount resulting from applying AASB2 standards to equity valuations for accounting purposes when a market-related vesting condition applies. For equity with non-market related vesting conditions such as Earnings Per Share Growth, the risk of forfeiture is usually comparable, although the AASB2 treatment is different.

Conversion of SIP Awards into Equity

Those parts of SIP awards that are converted into equity are typically subject to the following formula, which incorrectly ignores dividends:

Number of Equity Units = Value of Award ÷ Face Value of a Share

The face value is typically calculated as a volume weighted average price close to the time of the grant of the equity.

The same formula is applied irrespective of whether the equity units are FVEs, SVRs, or PVEs. Despite PVEs having a much lower value than the other two forms of equity units, due to the performance-related risk of forfeiture. GRG has not observed any situation where a different formula is applied. This approach has led to executives’ remuneration being lower than was expected or communicated.

Realisable Benefits

The following table illustrates the benefits that may be realised from a SIP at two performance levels (Target and Stretch) for the annual award and four long term performance levels (0%, 25%, 50% & 100% vesting) for vesting of the PVE. The key point to note is that the “earned” award communicated at the end of each year will be rarely if ever fully realised because full vesting of PVEs will not be a common occurrence, just as full vesting of LTI is not common.

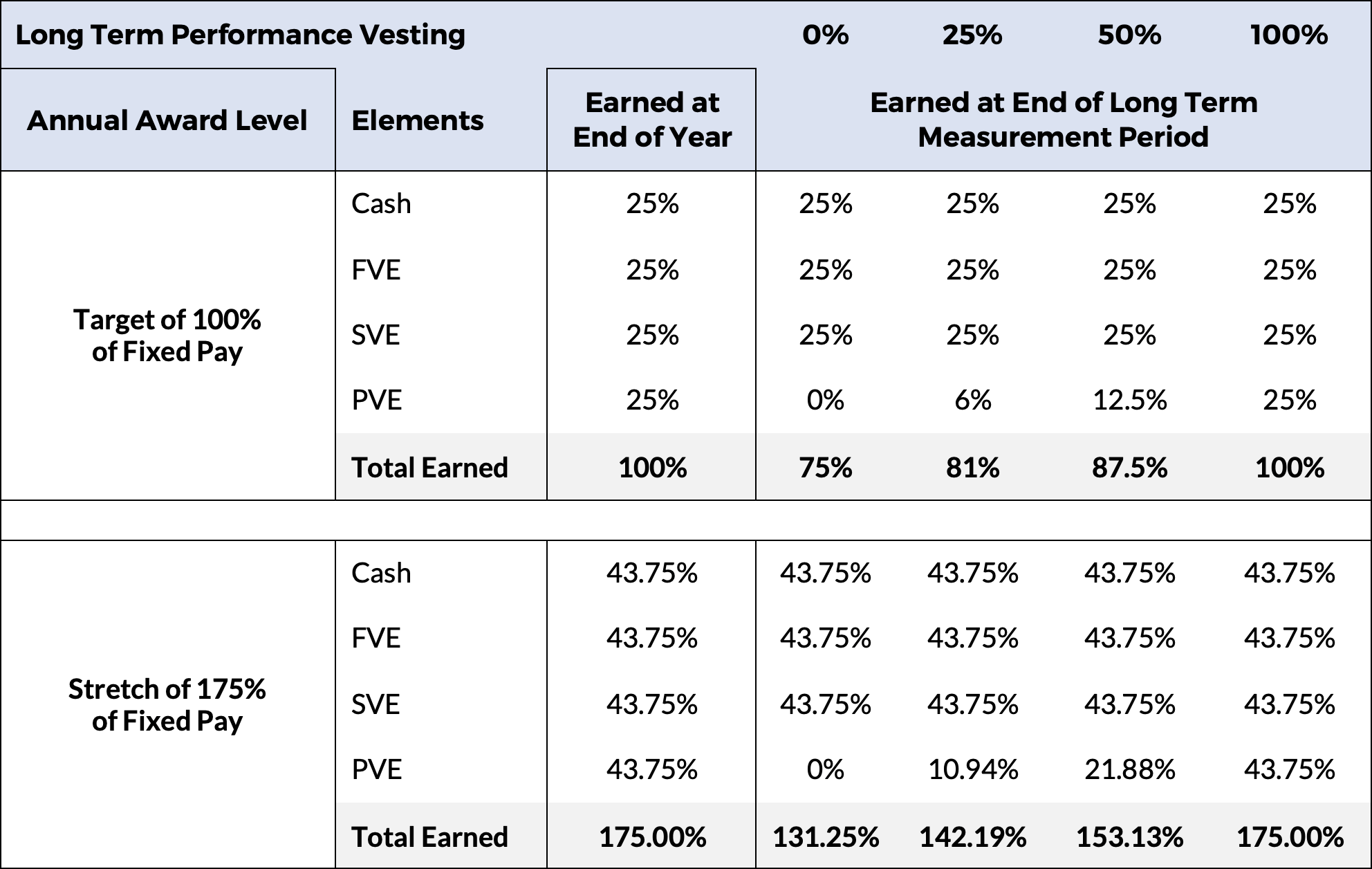

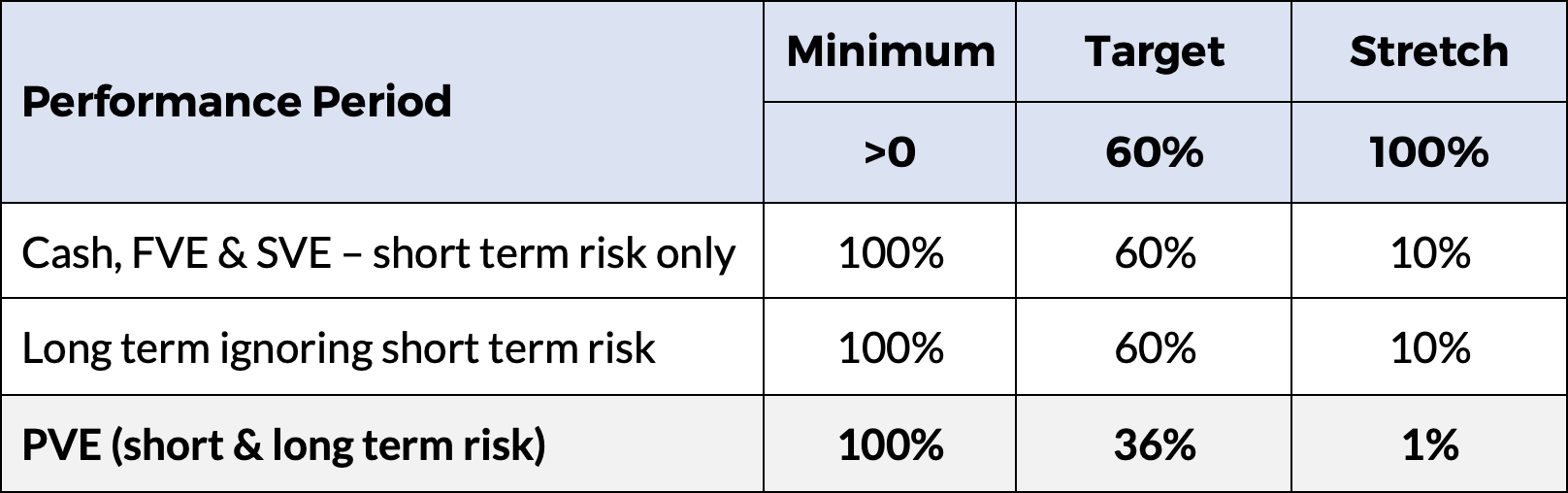

While it appears that the comparable stretch reward arises when stretch is achieved for both short and long term performance, the probability of this occurring is in fact much lower than under a discrete STI and LTI structure. This is because in order to achieve the stretch award, stretch performance must be delivered sequentially, as part of the same opportunity i.e. the probabilities multiply together. For an STI a typical risk profile would be say 60% chance of Target being achieved and 10% chance of Stretch being achieved. However, for SIP PVE the risk is compounded because similar risks would apply to vesting of the PVE grants that have already achieved the stretch hurdle over the short term. The combination of the short-term and long-term risks result in an approximate 1% chance of stretch reward being achieved, as illustrated in the following table.

In stark contrast, discrete STI and LTI opportunities have discrete probabilities and do not multiply together i.e., it is possible to achieve stretch LTI in a period when STI was at target; something which is impossible under a SIP.

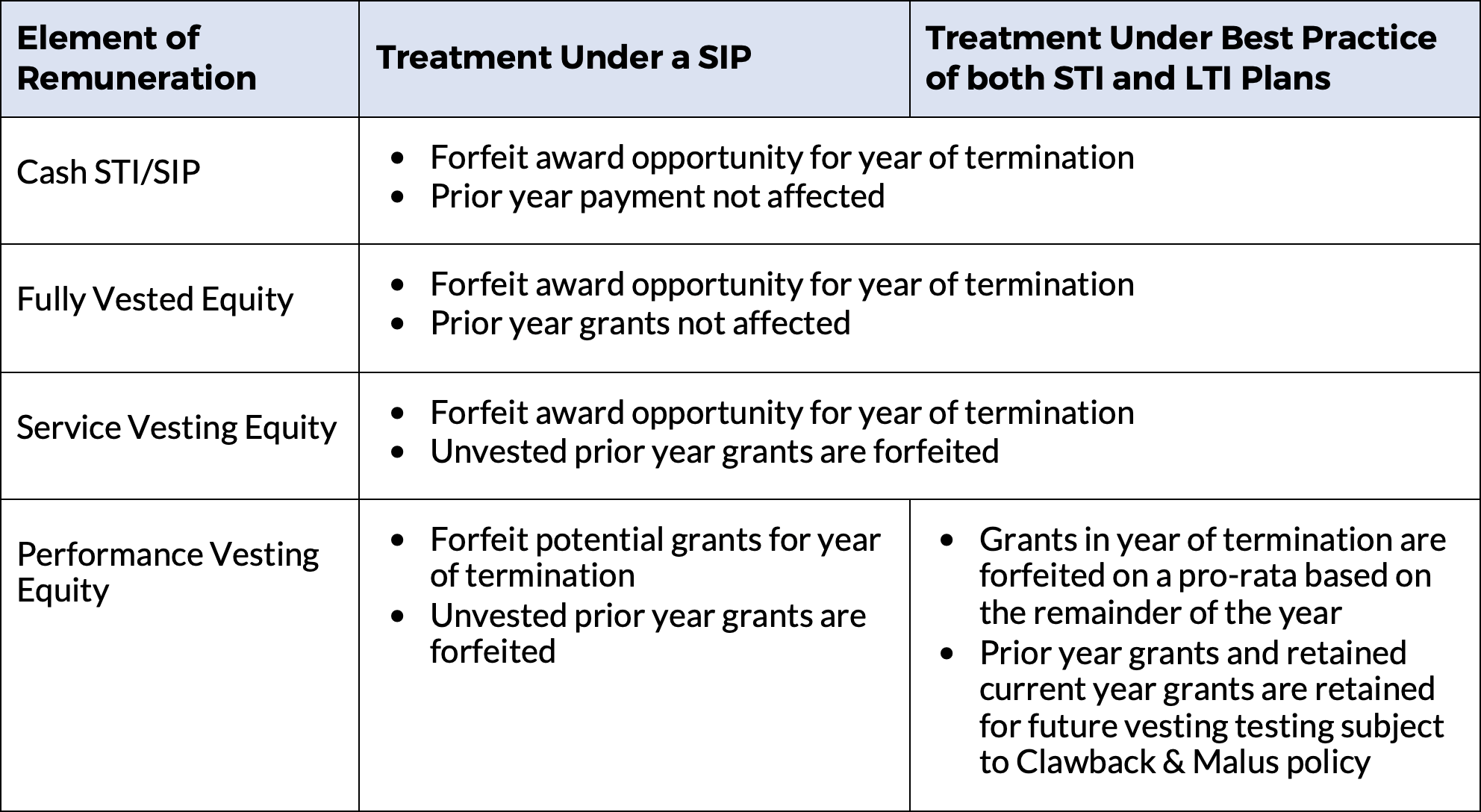

Cessation of Employment

Another feature of SIPs that leads to lower remuneration for executives is the treatment of SIP awards on cessation of employment. While there are some variations in market practices, the following compares a typical SIP approach with what GRG considers to be best practice in relation to cessations of employment during a financial year.

Even if SIPs changed the treatment of PVE to be consistent with best practice the problem of lesser remuneration due to forfeiture at termination would not be fully rectified because the PVE element of a SIP is much smaller than under the dominant market practice of STI and LTI plans. As such, much more of the variable remuneration is subject to full forfeiture at termination rather than remaining on-foot for long term outcome performance testing as should be the case for LTI. For companies that believe that forfeiture at termination is a powerful retention tool, this may be viewed as an advantage, however, market evidence is that service testing remuneration is not an effective retention tool for top executives. Instead, multi-year service testing tends to result in participants discounting the perceived value of the remuneration on offer (“psychological value”), noting that typical ASX executive tenure is now typically 3-4 years only. This therefore further substantially undermines the already weak long-term alignment of SIP structures.

Conclusion: SIPs add complexity for lower executive reward

SIPs were originally promoted as being much simpler than using STI and LTI plans. However, they added complexity and led to executives being paid less than expected.